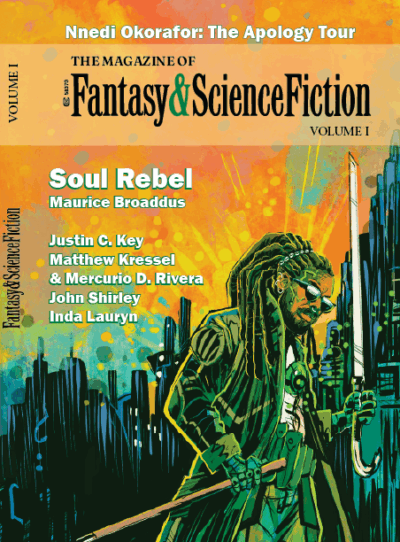

A better than average issue of F&SF

3 stars

A better than average issue, with interesting stories by Matthew Kressel and Mercurio D. Rivera, Justin C. Key, John Shirley and William Mangieri.

-

"Threat Assessment" by Matthew Kressel and Mercurio D. Rivera: an interesting story of a psychologist tasked to access the intelligence of an AI that may threaten humanity. What she discovers, instead, are lies and deceptions and a struggle to discover the truth.

-

"The Final Trial of Jalen, Oba of Uhuri" by Justin C. Key: a tale set in an African country at the time when slavery was rampant. The ruler of one country was disposed and sentenced to limbo by his sister, but now has a chance to return to reclaim his throne and try to end the slavery of his people.

-

"The Corporate Soul" by John Shirley: a scientist discovers a way to illuminate the 'soul' of a person, and has now been tasked to reveal …

A better than average issue, with interesting stories by Matthew Kressel and Mercurio D. Rivera, Justin C. Key, John Shirley and William Mangieri.

-

"Threat Assessment" by Matthew Kressel and Mercurio D. Rivera: an interesting story of a psychologist tasked to access the intelligence of an AI that may threaten humanity. What she discovers, instead, are lies and deceptions and a struggle to discover the truth.

-

"The Final Trial of Jalen, Oba of Uhuri" by Justin C. Key: a tale set in an African country at the time when slavery was rampant. The ruler of one country was disposed and sentenced to limbo by his sister, but now has a chance to return to reclaim his throne and try to end the slavery of his people.

-

"The Corporate Soul" by John Shirley: a scientist discovers a way to illuminate the 'soul' of a person, and has now been tasked to reveal the collective soul of a corporation (made up of members of its board) ahead of a vote to grant US Senate seats to corporations. But what he reveals may not be what the corporation may be expecting.

-

"The Apology Tour" by Nnedi Okorafor: a scientist responsible for creating sentient AI goes on a tour, to 'apologise' for effectively turning the AIs in virtual slaves for humanity. A personal crisis and a heart-to-heart talk with her own personal AI assistant inspires her to change her ways.

-

"The Seventy-Eight Spoons" by Devan Barlow: A woman visits the home left to her by her great-aunt, who was once considered the village witch. The spoons she finds in the house would lead her to discover a way to have 'fun'.

-

"And a Little Garlic" by William Mangieri: a fishing trip with some garlic would lead a fisherman to discover a talking fish, with their own ideas on merits of fishing.

-

"The Red River Summers" by Inda Lauryn: a Native American discovers she has powers that can help others. But she has to run from slavery and hides in a forest. Some people know of her powers, and come to her for help. With ever-growing development encroaching, she may not have a place to hide.

-

"Soul Rebel" by Maurice Broaddus: part of a series of stories by the author, this one starts and ends in the middle of a tale of attempted sabotage and a man trying to keep his son with unusual abilities safe from those who want to kidnap the son for their own purposes.